Livestock guardian dogs can do important work on farms. But they are being surrendered and euthanized in epic numbers.

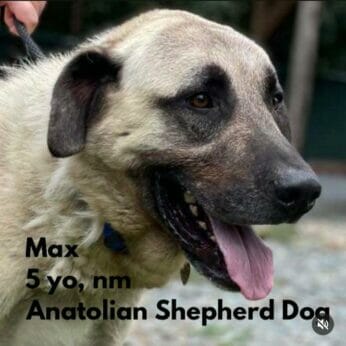

On the last Tuesday of August, a vehicle pulled into Providence Farm in McLeansville, North Carolina. Joy Combs had been expecting these guests—they were from the Carolina Great Pyrenees Rescue (CGPR), and they were there to drop off a five-year-old Anatolian Shepherd named Max. Combs planned to work with the rescue to evaluate his behavior with farm animals and help place him in an appropriate home.

Max had lived on a farm as a working dog before being surrendered by his owner to a shelter in South Carolina.

“The story that we had about Max is the story that we get about so many dogs,” says Rose Stremlau, vice president of CGPR. The reason given for Max’s surrender was that he wasn’t working out as a livestock guardian.

Max, an Anatolian Shepherd rescue. (Photography courtesy of Joy Combs, Providence Farm)

Livestock Guardian Dogs (LGDs) are inherently smart, independent and very big. Traditionally, they’re working dogs that protect livestock from predators. This type of dog encompasses several breeds, Great Pyrenees (colloquially called “pyrs”) and Anatolians like Max being two common ones. They are bred to be good workers, but they also require training to do the job well. These dogs are also often adopted as non-working family pets.

A big dog with a happy face, Max had gotten skinny from the stress of the shelter environment. Because of factors including excessive breeding and improper handling, dogs like him are being surrendered and euthanized at crisis-level rates across the country. Rescues, including CGPR, are doing everything they can, but, according to Stremlau, it is not enough.

“It’s like trying to push the ocean back with a broom,” she says. “Impossible.”

Trending dogs

CGPR was founded in 1992. In the early days, Stremlau says, it was able to take and rehome all of the pyrs it was contacted about, about 100-150 per year. In the first eight months of 2023 alone, CGPR has been contacted about more than 630 dogs. It does not have the resources to keep up.

Stremlau attributes the surge in owner and breeder surrenders to the emergence of the modern homesteading trend, saying that as more people began keeping backyard chickens or goats, many decided to get an LGD to protect their new livestock.

To be successful guardians for livestock, these dogs need guidance. Without being properly trained and bonded to their livestock, the dogs won’t automatically protect them. Instead of guarding your chickens, says Stremlau, an untrained dog may treat your chickens like a squeaky toy. And in the end, this results in people surrendering their dogs when they can’t figure out how to manage them. Snapping at, biting or killing farm animals is not a sign of a failed guardian dog but a sign that someone failed to train it.

“Those are all behaviors that are normal in puppies and juvenile guardian dogs that owners who know what they’re doing, [or] social, confident adult guardian dogs would correct if the dog was properly socialized,” says Stremlau. COVID-19 paired with a lack of animal welfare laws exacerbated the situation, along with irresponsible breeding by breeders trying to cater to the trend. CGPR used to mostly field queries about adult dogs, but now it’s not uncommon to see surrenders of partial litters of puppies. Stremlau says approximately a third of the dogs CGPR receives come from farms, and the others come from urban or suburban areas where the dogs were either adopted as family pets or to guard a small number of backyard chickens.

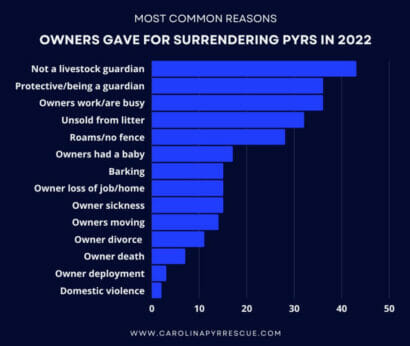

A breakdown of the reasons owners gave CGPR for why they were surrendering a dog. (Image by CGPR)

Official organizations such as CGPR have trusted contacts, such as Combs of Providence Farm, that it calls for help. Combs has five working dogs, and she’s been able to help take in three dogs so far this year. That’s a lot for a volunteer, but it pales in comparison to the number of dogs she gets contacted about.

One Sunday this summer, Combs was contacted about 10 different Great Pyrenees needing placement: three pairs of adolescents, a pair of older pyrs and a pair of puppies. Through the network of contacts, placements were found for the puppies and the older dogs. The six adolescent dogs were euthanized. There was just nowhere to put them.

In terms of making a dent against these numbers, Combs says it feels like sticking your hand into a bucket of water.

“Once you pull your hand out,” she says, “there’s no evidence you were even there.”

Too many to help

Jean Harrison is the founder of the Big Fluffy Dog Rescue in Tennessee. She doesn’t agree that the number of dogs needing rescue is increasing. She says that the issue was always this bad, but, thanks to social media, people have a growing awareness of rescues, so the rescue groups get called upon more often for help with dogs who need placement. Regardless of why it’s happening, Harrison says the uptick in surrendered dogs is overwhelming and there are not nearly enough resources or rescues to help them all.

“Every day, I get up and I live a sort of existential hell,” says Harrison. “Before my feet have hit the floor as I get out of bed, I know that I’m going to get 3,000-4,000 emails every single day asking for help with a dog.”

To illustrate the point, Harrison toggles over to her email inbox. “I have 26,312 unread emails right now,” she says. “And I will never get to all of them.”

A Great Pyrenees. (Photography by John Adams for CGPR)

Sue Innamorato is the director of intake for National Great Pyrenees Rescue and verifies the trend across states, saying the numbers are overwhelming and depressing.

Innamorato believes the uptick is due to the combination of multiple factors. She’s observed that the majority of owner surrenders the rescue receives are from farms, but it’s also not uncommon to see litters of puppies who need homes. In some of the states where the problem is the most critical, such as Alabama, California, Texas and Tennessee, she says shelters can see 15-30 Pyrenees per month.

The best things people can do, she says, are to spay and neuter their dogs, provide working dogs with consistent veterinary care and do their best to combat the “mountain of misinformation” about these dogs—such as that they don’t need to be trained or socialized to be good workers. Innamorato, who sees a deluge of Pyrenees who need homes on a daily basis, says she always remembers the ones the organization can’t save. With every dog, she says, it’s a race against the clock.

Gracie (left) and Optimus (right). (Photography by John Adams for CGPR)

Rescued

Despite his rough path to get there, Max, the Anatolian Shepherd at Providence Farm, is doing well. Combs says she has already received three applications for his next potential home. To combat feelings of helplessness, some LGD rescuers have learned to look for bright spots like this among even the most horrific stories. Earlier this year, Combs was on her way into Chapel Hill when her phone rang. It was a veterinarian who was asking for help with two dogs. After not being able to manage the dogs, the owner of the small farm where they lived had tried to euthanize them at home with prescription drugs. When Combs got to the dogs, they were alive but non-responsive.

One dog quickly recovered and got a new placement, but the other, a female Anatolian named Millie, had been hurt badly by the drugs. After six months and four foster homes, Combs and a rescue partnered to find her a perfect home on a farm for flowers and fruit, where she can be a property guardian mentored by two experienced LGDs. One morning at the end of August, Combs got a video from the new owner of the dog playing in the creek on the property for the first time. That feeling, for Combs, is unparalleled.

“I thought I was going to be the one holding her when we put her down because she was such a trainwreck. [She] was in such a bad way,” says Combs. “So, to get her in this place where I know that she is living her best life…it was just euphoric.”

What is happening to these dogs should be illegal

It has been my experience that they are the most loving and caring animals that I have ever seen and they need to be treated with the respect they deserve and a loving home

If my health was better I would get one in a heartbeat 💓

I own a Great Pyrenees who will be 11 yr old in Feb. She’s in good shape, but we want another Pyr that she can train. Ours work in our apple orchard and protects our chickens. I just told my vet that if he knows of Pyr that needs to be rehomed, to contact me. I want to bring in another before I lose my Pyr and her opportunity to train the new recruit. We will be sad to lose her; she’s a well loved dog who loves her job.

If Gracie was in Florida I would take her!!!

I’m a citizen that loves all dogs and hate what’s happening to them. I’m hoping to be a help possibly by fostering..

Not just guardian dogs. Covid encouraged many to get a dog and then people were surprised when they returned to work that their pets behavior changed. Many people don’t do their breed research. (Guardian dogs not only need to be trained but guard at night…Pyr are great at deterring coyotes but that also means alerting(barking). Not popular in suburbs to have a dog barking at 2 am AND the big problem……people willing to rescue or puppy raise ( for guide and service dogs) now live with draconian rules (San Bernardino County max 2 pets…2 dogs or 1 dog 1 cat).… Read more »

Max Update: Lucy and I adopted Max and added an “x” to his name because he is exceptional. Maxx has adjusted well to being the lead guard dog overseeing the night watch in our pasture. We lost a Great Pyrenees to cancer and the morning we put Finley down unknown to us Maxx was pulled from the shelter by CGPR. We had adopted through CGPR previously and had been in contact about Finley’s health. After Maxx was confirmed as an LGD at Providence Farm we adopted him with confidence that he was the right LGD for us. Hats of to… Read more »

Is there a way to get them to Seattle?

Hello!

I’m researching how to change laws around livestock guard dogs as I’ve witnessed an inhumane situation in Oregon and I came across your post. My local county won’t enforce anything because they are LGD. Do you have any information around these laws and what can be done? I’m trying to collect as much info as possible.