Despite Alaska’s size, farmland is still out of reach for new farmers.

Your mental image of an Alaskan farm probably involves a plot of land amid endless country, hemmed in only by distant, snow-capped peaks. Perhaps that image is informed by articles on “cheap” and abundant farmland in the far north or articles on how climate change opens opportunities by increasing the number of Alaska’s growing days. The 2017 U.S. Agriculture Census reports that farming in Alaska is vibrant and expanding rapidly.

For new farmers, this isn’t the whole story. Alaska is the country’s largest state, with an immense amount of wilderness, yet this creates a misconception that the state is one of the few places a new farmer can find affordable farmland.

“The idea that we are a land of plenty, in that regard, is incorrect,” says Phoebe Autry, who runs Sauntering Roots farm in Palmer, a city about 45 minutes north of Anchorage, and is the farmland conservation director at the Alaska Farmland Trust. Autry receives about three to four phone calls per month, as well as an email per week, from new farmers seeking land in Alaska. “About ninety percent of these people are from outside of Alaska,” says Autry. They expect land in Alaska to be cheaper, even close to major markets. Often, Autry has to dissuade them. For farmland near the largest markets in Alaska—the Mat-Su Valley and Anchorage—Autry says, “We’re looking at fair market values per acre of $25,000 to $40,000.” In 2021, the USDA listed the average value for an acre of farmland in California at $13,860. In Florida, it’s $7,300. In Kansas, it’s $2,100. It did not track values for Alaska.

Even farther north, farmers see similarly high prices. A new farmer might believe that the conditions in a town like Fairbanks would make farmland affordable. Much of it overlays permafrost, winter temperatures drop below -40 degrees Fahrenheit and the growing season is only four or five months long. Still, the Fairbanks North Star Borough lists “lack of available and affordable farmland” as a key barrier to increasing agriculture. Fairbanks farmer Brad St. Pierre puts it bluntly: “There is no cheap farmland in Alaska.”

St. Pierre runs a diversified, organic vegetable farm on a 75-acre plot with his wife, Christine. Having difficulty affording farmland in Fairbanks, the couple rents from a private landowner, about 10 miles from downtown. The farm is successful, and the St. Pierres were named the 2019 Alaska Farm Family of the Year. Yet, they are unsure whether the equity they build in the soil will be theirs down the line.

Brad St Pierre and kids. Photography courtesy of St Pierre.

Across the country, historically underserved farmers have the most difficulty accessing land. The U.S. Department of Agriculture includes in that category beginning farmers: those who have run a farm for 10 years or less. Like St. Pierre, whose family came to the U.S. from Cuba with only “their wedding ring and the clothes on their back,” these farmers rarely have family wealth or land.

Without a nest egg, new farmers turn to cheaper land. That comes with pitfalls. In the far north, more affordable farmland often overlays permafrost, which causes slumping and sinkholes when it thaws. A Fairbanks study notes that while climate change increases growing days which many are touting as a bright future for Alaska farming—warming also causes permafrost to thaw more rapidly, rendering portions of the land unusable. Glenna Gannon, assistant professor of sustainable food systems at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, says that “beginning farmers often don’t have a ton of capital at their fingertips, and they look at the land they can afford, not the land they need.”

Clearing land, using plastic for high tunnels and mulch and irrigation exacerbate permafrost degradation. “Those practices can be highly disruptive to permafrost, so we see an exponential rate of thaw and subsidence in the presence of some permafrost types,” says Gannon.

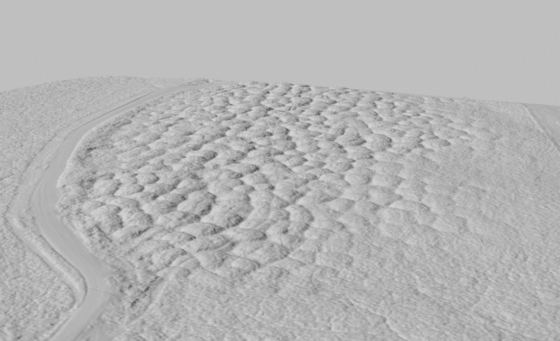

This LiDAR image shows “polygone formations” in a field near Fairbanks that was cleared in 1908 for farming and was abandoned by the 1920’s due to permafrost thaw. Image by Benjamin Jones

Ultimately, farmland close to the market is the most important to preserve because it keeps these costs and risks down. But farmland near town gets more expensive when it competes with residential and business development, two more economically viable uses. “We’re doing our best to preserve the best land that we have, [but] we’ve lost so much of it already,” says Autry. “We have a housing subdivision sitting on farmland that has 12feet of topsoil. It breaks my heart.”

It would be difficult for a new farmer to come to Alaska, buy farmland close to town and turn a profit in a reasonable time, says Sam Knapp, who runs Offbeet Farm in Fairbanks. Maybe if the farmers are “coming in with money,” Knapp says they might fare alright. Knapp’s farm is in a residential area on land he purchased with income from a second job and the support of his wife.

Second incomes are often critical for farmers in Alaska. This means less time to turn a profit on the farm. Additionally, what best prepares farmers for success, such as working someone else’s farm and studying for a degree, does not allow them to save money.

Such difficulties drive new farmers in Alaska to plots even farther from town. Like the land overlaying permafrost, these plots are cheaper to buy but more expensive to keep. Undeveloped land must be cleared and cultivated over years before planting a crop for sale. Remote land requires building water and power infrastructure, transporting goods to market and shipping in equipment and fertilizer. With such thin margins in farming, these costs are prohibitive.

Nels Christensen plans to farm 40 acres of his family’s allotment land, 145 miles northeast of Fairbanks in the sovereign nation of Gwichyaa Zhee, also called Fort Yukon. Allotments are part of a federal program that requires Native Americans to ask for land back that the U.S. government originally took from them. Christensen dreams of returning to Fort Yukon to farm that land, yet he is hesitant to start in a place far from infrastructure and markets. Although he has gardened since childhood, he started farming one year ago, at age 21. He predicts it will be “difficult to have stability and prosper” in Fort Yukon at this early stage.

Phoebe Autry. Photography courtesy of Autry.

There are USDA grants for beginning farmers and loans through the Farm Service Agency and the Alaska Rural Rehabilitation Corporation. The USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service and soil and water conservation districts provide free technical and financial support. Still, new farmers in Alaska find it difficult to own the land they farm. When farmers do not own, they owe.

Throughout the country, there is a high concentration of farmland in the hands of a few landholders who are aging out. The market incentivizes their heirs to develop it for other uses. Farmland wanes and new farmers cannot afford what is left. The nation’s largest, most wild state is no exception. The next generation of farmers cannot benefit from Alaska’s abundant territory if communities do not find ways to help them own and keep the land best suited for the job.

I couldn’t agree more. Less than 1 % of land in Alaska is privately owned to begin with. The odds of finding—let alone affording—a decent plot of land is abysmal.

Considering the challenges of finding affordable farms in Alaska, exploring cooperative farming initiatives or community-supported agriculture models could be a fruitful avenue to save money and promote sustainable farming practices. Collaborative efforts might offer financial benefits while fostering a sense of community resilience.”

Missing from this discussion is the Major problem of ‘wetlands’ regulations in Alaska. All permafrost is automatically categorized as wetlands, Although in some places it is underlain by gravel and will thaw and drain when Cleared, leaving behind very suitable soils for farming. But (wait for it) the Land cannot be cleared. Because it’s Wetlands. This is a huge Catch-22 and May very well be the downfall of the Big Nenana-Totchaket Ag Project being hyped by the Dunleavy Administration. The small print in the Project Info pages states that any ‘wetlands’ issues Must be resolved by whoever buys the Tract… Read more »