Steve Bushey’s passion for the humble weed is spurred by a love of native ecology.

Before dawn on an October morning, a thick fog wends its way down the many trails of Maine’s Peaks Island, coating the trees and fields in a gray blanket. A man makes his way along the trails, peering through the mist to admire the gardens kept by the thousand or so year-round residents. You might think that he is just an early riser on a casual walk, but Steve Bushey is on the hunt for milkweed seed pods of the common milkweed (asclepias syriaca), and he knows just where to find them.

Bushey and his wife, Angela Faeth, moved to Peaks Island more than 20 years ago. From their home, they run a map company that focuses on outdoor activities and documenting trails. As soon as he joined the small community, Bushey became the de facto trail guru for the many paths covering the island’s 750 acres in Casco Bay. In managing the trails, Bushey found himself focusing on the trees and bushes that grew alongside as much as the paths themselves. Peaks Island, along with the rest of the state, struggles with invasive bittersweet, honeysuckle and Norwegian Spruce.

That was the beginning of Bushey’s fascination with native and invasive plant species in Maine. He studied how they grew and ways to disrupt the growth cycle of the invasive plants to allow native species to thrive again. Then one day, he watched a documentary on the migration of the monarch butterfly.

At first, he did not connect the needs of monarch butterflies and their 2,500-mile migration to his work on Peaks Island. The monarchs’ travel takes them from the northern US and Canada to their breeding grounds in Mexico, and the trip spans generations of butterflies. They rely exclusively on milkweed plants to sustain their migration and feed each generation of monarch caterpillars. There are 73 varieties of milkweed growing in the United States, more than 30 of which are hosts for the monarch butterfly and its caterpillars. It contains a chemical compound called cardenolide, which is toxic to most would-be predators. This provides the caterpillars safety from being eaten, and it remains in the bodies of butterflies after they transform.

A monarch caterpillar (left) and butterfly (right). (Photos courtesy of Steve Bushey)

The population of monarch butterflies has declined by more than 90 percent since the 1990s. This is partially due to logging in their overwintering grounds in Mexico and severe weather during their migration. But studies suggest that a downturn in the nation’s milkweed supply has been the leading cause of the dramatic decline in the monarch butterfly population.

The toxin of the milkweed makes the plant incompatible with fields hosting grazing cattle or intended for hay, and milkweed is renowned for aggressive growth that chokes out field grasses. This makes it a natural enemy of many farmers, who deploy herbicide sprays to eradicate the plant.

Fascinated by monarchs, Bushey thought about going to Mexico to see the butterflies in their breeding grounds. Then he realized he could help them on their journey from his backyard in Maine. “I flipped it around, and I thought it has to be a terrible journey trying to work your way down the East Coast through all those urban areas.”

“I had a lot of conversations with people on the island,” says Bushey. “I became an advocate for the bees and the butterflies. I became an advocate for encouraging people not to pull up the milkweed and to plant native flowers.”

Bushey was immediately impressed with the resilience of the milkweed plant. “Milkweed is an aggressive native grower,” he says, admiring how it can appear in disturbed areas of soil and how one seed can give rise to a plant that, through rhizomes, spreads into an entire cluster.

With his experience in mapmaking, Bushey recognized that he could help the monarch butterflies from home through propagation of the milkweed plant. He started to track where milkweed was growing on Peaks Island. “On my morning walks, I began mapping the locations of all the milkweed patches I could find,” he says. “I spent three or four weeks doing these long walks, poking around corners and talking to people in their yards.” Using GPS mapping technology, Bushey came up with more than 60 locations of milkweed patches on the island. And he noticed something interesting: “There were not many wild locations where milkweed was growing. Most locations were in gardens.”

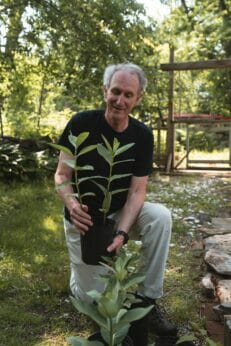

Steve Bushey with a milkweed plant. (Photo: Sarah Bryant)

Bushey was determined to expand the milkweed options for weary butterflies, and so as the monarchs began their fall migration and the milkweed went to seed, he turned from mapmaking to seed saving.

“People would pick their milkweed pods and hand them to me in brown paper bags,” he says. “I had one woman stop me in the middle of the street to hand me a bag from her car window into mine—it probably looked like a drug deal, but I was just receiving pods.” Bushey ended up receiving hundreds of pods.

Milkweed seeds are dried and stratified within their pods in the natural temperatures of a Maine winter, which helps the vitality of the seed. The seeds take five to six weeks to dry, and they can be laid out on screens or strung between rafters in a barn or shed, leaving plenty of room for air flow around the pods and allowing for the temperatures to drop naturally. Eventually, the pods begin to crack open, releasing their seeds. At this point, the seeds can be removed from their “parachutes”—the soft white fluff that allows them to blow and spread on the wind.

Bushey sees seed pod gathering as an opportunity to foster community and intergenerational connection. “You can go outdoors and watch milkweed grow,” he says. “Watch the caterpillars, then the chrysalis, and at some point the butterfly comes out, and then you can start collecting the seed pods. Keep it within your community—so learn where to find the seeds, talk with people, get people to give you seed pods.” After the seeds are collected, the fun starts. “You can have seed parties, which can be messy but are great fun for kids. Then you can all make packages. It’s a lot of handwork—you can’t make money at this, but it builds friendships and a bond between the older generation and the youngest.”

Milkweed plants (left) and Bushey’s seed packets. (Photos courtesy of Steve Bushey)

Bushey did not just dry, store and spread seeds for himself. To encourage milkweed growth across Peaks Island and the state of Maine, he started selling packets of milkweed seed. He took homemade seed packages to his local garden center where they set a display up at the register, and he shared the packets with anyone interested in growing milkweed. Before long, many of the gardeners of Peaks Island had started milkweed in their seedling trays.

For residents of New England, Bushey is happy to share milkweed seeds for pollinator gardens. Just reach out through the email contact at MapAdventures.com, he says, and he’ll put a packet of seeds in the mail for you. He prefers to keep his seed packages within New England so as not to introduce common milkweed to areas where it is not native, and he recommends researching on which variety native of milkweed monarchs feed in other regions.

Now the milkweed man of Peaks Island, Steve Bushey’s vision for the life-giving weed goes much further than Casco Bay. He imagines a world where milkweed is no longer seen as a weed but as a favored flower and connection point between generations of gardeners and seed collectors.

“The monarchs’ journey is a multi-generational journey,” he says. “They die along the way and they have to lay their eggs and hatch butterflies, and it’s the next generation that makes it to Mexico. Imagine three generations of humanity sitting around a table talking, helping another species on their multi-generational trip.”

I live in northern Nevada and became interested in monarchs after a workshop on monarchs in 2014. I have a lot of milkweed in my garden, mostly showy milkweed or Asclepias Speciosa. Narrow milkweed or Asclepias Fascicularis is the other milkweed native to my high desert area. I collect a lot of my seeds from my garden and try to distribute them because patches of milkweed are rare in my locality which is basically rural with fields of cows and crops.

Here is a picture of my showy milkweed.

I was so excited to read about Steve. I live all the way across the US in Central California. We have a famous Monarch gathering eucalyptus grove that folks come from all over to see. Our Monarchs come in the fall. I decided to start a pollinator and Monarch garden years ago and now have my Daughters of the American Revolution involved as I share my seeds and what I have learned in working toward conservation of our butterflies and pollinators. I so appreciate your amazing efforts. Sincerely, Leisa from California

I’ve saved milkweed seeds for years. Plant them along front of my property. The rest is taken for a road trip. I drive the back roads near my house and release the seeds (about a five gallon bucket) into the wind and let nature take it’s course.

This a really cool article. I grow butterflies down in Florida I am living in the Ocala national Forest I am growing tropical and giant milkweed as we speak I don’t get very many monarchs here which I should get quite a few but I guess they have cleaned out all the milkweed that goes in the area the lady who taught me how to grow butterflies we would hunt them in forests more towards that West Coast. Now that I am paying attention to when they come through and how many caterpillars do I actually see I don’t get… Read more »

God bless him and his loving efforts.

I love monarchs. We have naturalized much of yard for years while living in Pa. . Recently we moved to 10 acres of undeveloped land full of wild flowers and milkweed in upstate NY. We disturbed the land only enough for a modular home and utility building.

This is a wonderful story. However, I was surprised to read the last paragraph. I live in Nova Scotia. Our Monarchs leave here in the late summer-“early autumn, and fly all the way to Mexico. One generation only. It is in the spring, when they awake from their diapause, that they begin their journey to their summer locations. THAT is the journey that takes four generations.

I found Showy Milkweek in the space between my garage and neighbor’s fence. It just came up one year and the blooms were so pretty, I left it. I’m hoping some really cool butterflies find it!

Is there a Steve Bushey in our area of Collier County Florida? If so how would I get in touch with them so I can start my journey with the Monarch Butterfly.Please keep me informed on this matter. Thank you and good job guys!!

Great article, learned some things.