Land ownership on the Winnebago Reservation had gone in only one direction—away from Native tribes and farmers. Until recently, when several tribes decided to change that.

Aaron LaPointe sits behind a desk in the Little Priest Tribal College’s library basement in Winnebago, Nebraska, ready to speak to a class in a new program he helped develop: diversified agriculture.

He’s here, on this 100-degree August day, to show high school and college students—the future of the Winnebago Tribe—how Ho-Chunk Farms, the tribe’s farming company, is changing the face of agriculture on their reservation.

“When you asked a student at my high school what a farmer looks like they would tell you a white guy with cowboy boots and a cowboy hat on,” said LaPointe, senior director of business operations for Ho-Chunk, Inc. “They didn’t see themselves as farmers, they just thought that’s what the white guys do. And we just let them use our land to do that.”

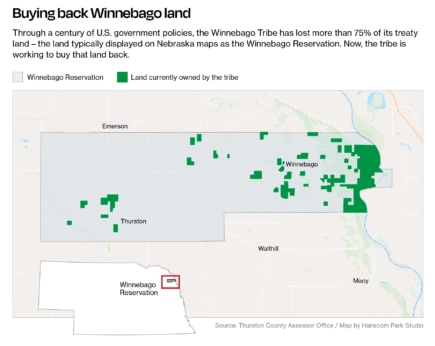

That perception is rooted in a century of reality. The tribe only owns roughly 27,000 acres of its 120,000-acre reservation, after U.S. government actions directly or indirectly led its farmland to pass into non-Native hands— mostly white farmers.

But that reality is starting to change. In the past five years, three Nebraska tribes—the Winnebago, the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska and the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska—have bought a combined 3,000-odd acres of farmland that was once theirs.

These buybacks aren’t cheap or easy. Tribal leaders say landowners who know that tribes want the land back believe they’ll pay any price.

And all three tribes are paying higher-than-normal prices, according to a Flatwater Free Press analysis of data gathered by a University of Nebraska-Lincoln journalism class.

The Winnebago Tribe spent nearly $10,000 per acre, on average, to buy back 340 acres of ag land. That’s about $3,000 higher than the northeast region’s 2022 average.

Tribal leaders think the higher prices and headaches are worth it.

“We want to start farming our own reservation. We want to own our reservation again,” LaPointe said.

Ho-Chunk Inc. Farms begins spring tilling on tribal land near Winnebago on April 20, 2020. (Photo by Jerry L Mennenga for the Flatwater Free Press)

Reservation, not reserved

After the Civil War, the United States government tried to upend the way most Native American tribes lived—including the way they viewed land.

The Dawes Act, passed in 1887, tried to force assimilation by splitting the previously communally owned reservation into 160-acre pieces of farmland, individually owned by tribal members.

The government then sold the leftover land to non-Native settlers.

“At one point we owned 100 percent of our reservation, until the federal government thought ‘Oh, this guy’s got maybe too much land, let’s take some of that from them,’” LaPointe said.

Native Americans had no concept of land as property, said Ted Hibbeler, UNL Tribal Extension Educator and member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe. Tribes built relationships with land over thousands of years but didn’t view it as a form of money or power.

More reservation land was lost when tribal members grew financially desperate.

One example: After the land allotment, members of the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska who couldn’t afford food were convinced by a White Cloud, Kansas, grocer to sign over their land as a promise to repay.

“They needed food, and that’s just what they had to do,” said Tony Fee, secretary of the Iowa Tribe. “This individual got them to sign it over as collateral … and they never could afford to get it back. So they lost it.”

Today, the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska owns about half of its 12,000-acre reservation, with Native and non-Native land ownership checkerboarded throughout.

On the Winnebago reservation, many families lost their land back paying unfamiliar taxes, or sold the land to cover medical bills, LaPointe said.

In 1934, the US government put all remaining Native-owned allotments into an indefinite trust. By that point, an estimated 90 million acres had been removed from Native ownership, according to the Indian Land Tenure Foundation.

Land ownership had gone in only one direction—away from Native tribes and farmers. Until recently, when several tribes decided to change that.

Ho-Chunk Farms senior fields operations supervisor Jeffery Thomas begins planting a soybean crop in the Big Bear Valley near Winnebago on May 2. (Photo by Jerry L Mennenga for the Flatwater Free Press)

Sticker shock

In the past few years, in addition to other larger purchases, the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska bought 4 acres next to some land it already owned. The Ponca Tribe of Nebraska made a 36-acre purchase.

Neither is notable, except for the price tag: More than $43,000 per acre.

“I don’t see too many places where anything approaching that happens,” said Cris Stainbrook, Oglala Lakota and president of the Indian Land Tenure Foundation. “I mean, $40,000 an acre is a lot.”

Farmland prices in Nebraska have risen across the board in recent years. According to UNL’s 2022 Nebraska Farm Real Estate Report, where the Winnebago and Iowa are buying, average acre values for high-quality land are around $7,000.

Those tribes often pay far more than that. In fact, every piece of reservation land the Iowa Tribe buys is priced higher than what similar land sells for, Fee said.

Racism is an underlying reason for higher land prices, Stainbrook said. He has seen sales where the asking price dropped dramatically when a non-Native organization was the buyer.

“When we’re helping (tribes) get land back there’s this underlying thought that if the tribe wants it bad enough, they’ll pay anything for it, or they must have a casino somewhere and therefore they can afford to pay more,” Stainbrook said.

Sales on tribal land are sometimes disincentivized by existing tax policies, like capital gains, LaPointe said, because the original sales happened for such little money that the taxes would be disproportionately high.

Ho-Chunk Farms manager Aaron LaPointe helps other employees and members of the Winnebago Tribe of Nebraska harvest corn Sept. 5 near Winnebago. (Photo by Jerry L Mennenga for the Flatwater Free Press)

But tribes shouldn’t be paying more because of the current owner’s tax bill, Stainbrook said.

“Do you think they sell it to another non-Indian and tell them, ‘Well, you’ll have to pay X amount more because of our capital gains’?” Stainbrook said.

Another reason for high prices: High demand.

One of the last pieces of reservation land the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska bought was offered to another individual right before the sale, Fee said, so the tribe’s only option was up their offer to get the land.

“They got us over the barrel if we want it. I mean, then they know we want it. We want it bad enough. We’re gonna pay for it,” Fee said, “To me, that’s not the right way, but we really don’t have a choice.”

The Iowa Tribe didn’t have many opportunities to buy land four or five years ago, when values were cheaper. Now that prices have risen, sellers are offering up land—if the price is right.

“The tribe does feel that we should do everything we can to try to get the land back,” Fee said. “And we’re just doing what we can to work toward that.”

Food as sovereignty

For Trey Blackhawk, manager of the nonprofit Winnebago Tribal Farm, acquiring more farmland is a way for the tribe to feed itself without relying on outside sources.

The farm, founded in 2018, grows fruits and vegetables on a 40-acre plot, as well as traditional Indian corn used in ceremonies. In the next decade, Blackhawk hopes to open a food co-op for the tribe.

Right now, the nearest grocery store to the Winnebago reservation is in Sioux City, Iowa. Tribe members drive up to 30 miles each way to get their groceries.

Winnebago Tribal Farm manager Trey Blackhawk seen at the farm outside of Winnebago on Sept. 14. (Photo by Jerry L Mennenga for the Flatwater Free Press)

“I think the pandemic helped people realize that we’re not very sovereign. We can’t even feed ourselves, really,” LaPointe said. “All these shortages were happening and we’re like, geez, we’re really dependent on a lot of people for our food sources.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, 49 percent of Native Americans and Alaskan Natives experienced food insecurity, according to a Native American Agriculture Fund survey.

Investments in Native agriculture help tribes to keep food production local so they can support their communities, said Whitney Sawney, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and director of communications and policy for NAAF.

The Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska farms about 4,500 acres of their land, Fee said, with the goal of food sovereignty.

The tribe is moving toward regenerative agriculture, using native plant species, natural fertilizers and beekeeping to grow nutrient dense foods.

Local tribal school children visit the Winnebago tribal farm to learn about planting and animals on April 22, 2022, near Winnebago. (Photo by Jerry L Mennenga for the Flatwater Free Press)

On the Winnebago reservation, LaPointe often visits classes at Little Priest Tribal College, presenting farming as a way to feed the tribe – and a good career opportunity.

LaPointe, 32, is the second oldest Ho-Chunk Farms employee. Young tribe members are becoming interested in agriculture. LaPointe believes they can be the next generation of farmers.

“That’s why I say land acquisition is so important for us, because our growth is dependent on it,” LaPointe said. “If I’m going to create jobs for this next generation of people that are getting educated in this field, we need to be moving forward by growing our acre base.”

The Flatwater Free Press is Nebraska’s first independent, nonprofit newsroom focused on investigations and feature stories that matter.

This reporting is part of a collaboration with the Institute for Nonprofit News‘ Rural News Network, and the Energy News Network, Flatwater Free Press, Mississippi Free Press, New Mexico In Depth, Religion News Service and Sierra Nevada Ally. Support from the Walton Family Foundation made the project possible.

Self sufficiency is the key to freedom. Return to old indigenous ways will benefit the earth

Assuming it is legal, the Tribe should use an agent to purchase land, thereby hiding the true buyer. They could also create a separate corporation/company to buy the land, and hide the true owner. Each purchase should be done by newly/formed, wholely owned subsidiary, so that each sale is to a separate entity. The tribes need some saavy attys, IMO