Two US companies have been given approval to sell lab-grown chicken. They say it’s a way to eat meat without the inhumane conditions of factory farms. But detractors say the hype over cell-cultivated meat is overblown.

Josh Tetrick swears he’d have another job if only all poultry producers farmed thoughtfully and could keep up with the appetite of a growing global population. However, of the more than 230,000 chicken farms in the US alone, the majority would be considered factory farms—something that doesn’t align with Tetrick’s vision of thoughtful farming.

Yet that tension between the global appetite for chicken and the conditions of mass poultry farming is also an opportunity for problem solvers at the forefront of one of the more audacious—and controversial—developments in the food industry.

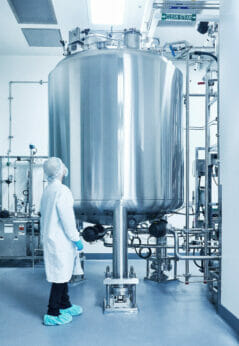

The lab at Good Meat. Photography by Good Meat.

Tetrick is the co-founder and CEO of Eat Just, which operates Good Meat, one of two companies approved by the USDA in June to begin selling cultivated, or lab-grown, chicken in the United States. The big idea: Create chicken meat in a controlled setting, with no harm to animals and a drastic reduction of the issues associated with problematic factory farming practices.

“We think that if you look at the last 50 years, the more traditional American farmer-rancher has been pretty decimated by large industrial operations,” says Tetrick. “So, our focus is how does cultivating meat ultimately replace a large-scale production of animal protein?”

But not everyone agrees that cultivated meat should replace traditionally produced animal protein. Among its critics is the World Farmers’ Organisation (WFO), representing more than 1.2 billion farmers globally, and which in July released a statement taking “a resolute stand” against lab-grown food. In the release, the WFO claimed cultivated livestock products “are supported by marketing campaigns that enhance the myth of greater sustainability compared to agriculture” and asserted that “there is no reliable evidence to compare cell-based food to farmer-produced one.”

“For us, food comes from the work of farmers, and we don’t think that these companies developing these products will stop just to be two or three percent of the market,” says Paolo Di Stefano, facilitator of the WFO’s Value Chain Working Group. “The idea that one day agriculture—natural agriculture, land-based agriculture—could be replaced by artificial food is quite difficult for us to accept.”

Farmers have every right to be concerned, whether it’s about the authenticity of cultivated meats or their own livelihoods. Automation and the uber-expansion of factory farming have increasingly limited the ability of others to compete in the marketplace. Many skeptics view lab-grown meat as a kind of Frankenstein-ing of food—an “unnatural” practice.

Photography by Good Meat.

Although proponents argue that a shift to lab-grown practices can dramatically lower greenhouse gasses, as well as reduce both land and water usage, some detractors claim that cultured meat may actually be worse for the environment than the real thing. What we know is that the cultured meat industry remains in its infancy, so research about complex long-term environmental ramifications is still limited. Lab-grown meat producers know that part of their industry’s value proposition hinges on improved environmental outcomes and more sustainable resource management.

Tetrick says his company has no interest in squeezing out small-scale poultry farming operations that favor sustainable and humane methods. He believes there will always be a market for animal-harvested meat done right. Rosanna Bauman, whose family runs Bauman’s Mobile Meat Market in Garnett, KS, seems to fall into the category of small-scale, “thoughtful” farmers that Tetrick describes. Bauman’s raises its chickens on pasture, with non-GMO grains, and its beef, pork and lamb on grass. They also hand-butcher their products and sell them direct-to-consumer at farmer’s markets and pop-ups. Bauman says she has heard “a lot of skepticism” from her customers about cultivated meat.

“Specifically, they weren’t sure that they wanted to be eating cultured meat and whatever it may or may not consist of,” says Bauman. “They were concerned about how it was presented to consumers … about how it was labeled or could be labeled.”

A chicken pot pie with lab-grown chicken. Photography by Good Meat.

Justin Kolbeck, co-founder and CEO of Wildtype—a company that makes lab-grown salmon—agrees with that sentiment. “I think the onus is on [companies like] us to communicate transparently, to have conversations like this, to talk about how the technology works,” says Kolbeck. “And, of course, our food products are just as susceptible to things like salmonella and listeria, that are sort of human-born and environmentally born. So, we need to have a very careful eye on food safety, just like any other conventional food company.”

In fact, Kolbeck says Wildtype, per an FDA request, conducted a DNA alignment test using the four nucleotides of Coho salmon samples, to test how similar the lab-grown salmon was to a freshly caught fish. “Lined them up, one by one, and just showed that it’s the exact same DNA that we found in conventional Coho salmon.” A person with a seafood allergy, says Kolbeck, would react to Wildtype’s product exactly as they would to the fish plucked from a stream.

Tetrick describes Good Meat’s chicken as the genuine article, even though it starts with a cell biopsy in a stainless steel vessel rather than an egg in a coop. “You feed the cell the same way that a farmer would feed a chicken,” says Tetrick. “Amino acids, vitamins and minerals. This is creating the conditions for the cell to grow in the same way that an animal’s body would create the conditions for cells to grow.”

Although some farmers follow more ethical animal welfare practices than others, cultivated meat—which removes slaughter from the production process, a key step—is indisputably more humane. Compared to traditional farming, the sustainability of lab-grown foods and the natural resources required to create cultivated meat is still in dispute—but is also constantly evolving as techniques are improved. Tetrick also notes that the controlled environment in which lab-grown chicken is created prevents diseases and other risks to consumers.

As for the overarching issue—is it natural?—Tetrick reorients the question: “Let’s just talk about that word: natural. I would ask, ‘Do you think chicken that is produced in the United States—99 percent of it—do you look at that as natural?’” Tetrick references chickens raised in jam-packed, sunlight-free structures, pumped with antibiotics and bred for maximum meat-bearing over the shortest time frame possible. There is a reason that chickens and eggs produced by factory farms today look and taste differently than products found on the market 50 years ago.

Cultivated meat advocates say lab-grown chicken offers the possibility of large-scale production with fewer required resources, less suffering and more control over the final product. But even its biggest champions admit that it won’t happen overnight.

“It is real chicken,” says Tetrick. “It’s just made in a way that doesn’t require the live animal to be a part of the production process. And because it doesn’t require the live animal to be a part of the production process, we think, ultimately, that we can make a lot more of that less expensively. Now, that’s a long journey to get there.”

That extended timeframe is both a boon and a worry for traditional farmers. “We don’t know today what the impact will be, because it’s not going so fast—the development of these alternatives—because of the cost of production,” says the WFO’s Di Stefano.

Chef Jose Andres cooks with lab-grown chicken. Photography by Good Meat.

Yet one sticking point remains: the ick factor. Some eaters may never have the stomach for lab-grown meat. At the end of the day, will enough consumers bite?

Some already are. Cultivated chicken hit the market in Singapore more than two years ago, and this month, in Washington, D.C., it lands on the menu at chef José Andrés’ China Chilcano. Supplies are limited, and the price tag (a reported $70 per person) is sure to turn away some eaters. But cultivated meat producers are already receiving heavy investment from venture capitalists (and, notably, factory farms themselves), and it may be only a matter of time before lab growers unlock the components for scaling up production.

“At some point, are we using too much of the earth just for the animals we eat?” says Tetrick. “Longer term, that’s how you can make billions of pounds at the lowest possible cost in a way that just doesn’t require so many resources—so many hundreds of millions of acres of land and trillions of gallons of water. That’s where we see this going.”