A critical global crop, rice makes up roughly 20 percent of calories consumed by humans, but it’s highly dependent on getting the right amount of water. Can it be bred to survive the changing climate?

In one of the greenhouses on the Lundberg Family Farms acreage in northern California, there sits a binder. Technically, there are multiple volumes of the binder, as it’s grown significantly over the years. The binder contains the thousands of different varieties of rice with which Lundberg growers have experimented, bred from and either liked or discarded, along with notes on all of the above. When I visited the farm in late 2022, research supervisor JP Bergmann showed me the 40 varieties on which they were then focused in their breeding program. Those varieties get tested against each other and the rice the Lundbergs currently grow, and they can get interbred in nearly infinite variations.

It can all get out of control very quickly without some organization and focus. Hence, the binder.

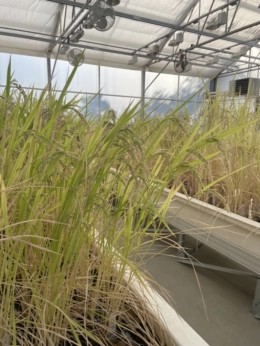

Rice growing in one of the Lundberg Family Farms test greenhouses. Photography by author.

Rice is a critical global crop, responsible for about 20 percent of the calories people consume. Crucial to food security, we’ll have to both protect and invest in rice within our food system as the population grows.

Rice is also a crop that is highly susceptible to extreme weather, especially changes in water availability. Too little water, like farmers often deal with in California, is not good. It can take around 2,500 liters of water, through both rain and irrigation, to grow one kilogram of rice. So, breeding more efficient rice requiring less water is a big win for drought-prone areas.

Conversely, too much water is also a bad thing when it comes to growing rice. While rice can grow well in a paddy, especially compared to other cereal grains, there is a limit to how much water the plant can bear and for how long.

Lundberg grows more than 13,000 acres of certified organic rice, along with another 5,000 acres of conventional rice, and that all gets turned into dried goods such as rice cakes, chips, risotto and, of course, rice blends. When the company’s leadership wants a more vigorous Basmati variety or decides the short grain brown rice didn’t yield as much expected, they go to Bergmann and JJ Jiang, the nursery manager and plant breeder, with a goal.

After testing the germplasm of new rice varieties in their greenhouse, Bergmann and Jiang plant a small batch in one of their test fields, taking notes throughout the season to build up their binder of statistics. Each field test is also a multi-year process, as they let the rice adapt to the growing conditions. Bergmann says they particularly focus on qualities such as weed competitiveness and drought tolerance. “We do look a lot at rice varieties that are going to have good root structures that give them resilience to dry up periods, so they can withstand those periods of time where we’re not putting water out to the field,” in an effort to make the rice resilient to a wide range of environmental conditions.

“Breeding rice is a formidable task,” says Jiang. He calls the work “experimental design,” in that it’s not haphazard, but you do need to test out a lot of options before finding the one that works for you. “And there’s no standardized quality criteria (for rice.) It’s all up to us.” That means growers have to factor in multiple competing traits while also accounting for flavor, taste and consumer trends—not to mention changing environmental factors.

Cross-breeding rice at Lundberg Family Farms. Photography by author.

Under water

Pamela Ronald, a professor of plant pathology at the University of California, Davis, has spent years working to develop rice with a high submergence tolerance. “Most rice varieties form well if they’re in standing water, but they’ll die if they’re completely submerged in water for three days,” says Ronald. This is a big concern for rice-growing regions in which flash flooding and tsunamis are occurring more regularly, such as Bangladesh, Vietnam and India. Ronald says it’s estimated that four million tons of rice—enough to feed 30 million people—is lost to flooding each year. This is a problem that is going to get worse in the future, as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicts that flooding will increase in both frequency and intensity going forward.

In 1995, Ronald’s lab isolated a gene for submergence resistance that is now used by rice growers throughout India and Bangladesh, among other areas, with success. Her work has continued to help the crop in disease prevention, and in 2022, she was awarded the Wolf Prize in Agriculture for her contributions to humanity. “More than six million farmers are growing the [submergence-tolerant] rice, and they have a 60-percent yield advantage in some places in the world, such as eastern India,” says Ronald. “It’s benefitting the poorest farmers in the world.”

When rice doesn’t get the right growing conditions, it’s also more susceptible to disease, such as phytopathogenic bacteria, which can significantly reduce yields. At the University of Missouri, Bing Yang, professor of plant science and technology, has used CRISPR to edit samples of the bacteria to determine which genes had the qualities that would infect rice crops, to help breed rice that is more disease resistant. “Bacteria usually have some weaponry or some factors which they employ to infect a host plant,” says Yang. Figuring out which genes those are, and then working backwards, can help determine which genomes in the host plant may need strengthening. “Farmers and breeders always want high-yield rice and, at the same time, try to breed a high-temperature tolerance or a high-salt tolerance. People are always turning to science to identify the beneficial genes which could give them an advantage.”

An Arkansas rice field. Photography by Shutterstock.

Field work

Although California produces about half a million acres of rice a year, it’s only the second-highest rice producer in the country. The top honor goes to Arkansas, at nearly triple that output. In fact, Arkansas rice producers grow almost half of all rice in the country.

And while they don’t have the same complicated system of dealing with water as producers in California, they do have to contend with water and what’s naturally available all the same. Mark Isbell of Isbell Farms in central Arkansas is a fourth-generation rice farmer who’s watched the boom-and-bust cycle of rice growing get more erratic in recent years. “Two years ago, we had a massive flood that was fairly devastating to a good portion of the crop. And then last year was a pretty deep drought, which we were able to irrigate,” recalls Isbell. Isbell, and his father before him, have tinkered a bit with breeding in their rice crops, but most of their interventions have been more tactile. They have worked to adapt their 3,500 acres to make them more water efficient as the resource has become more scarce.

First, they carefully precision-leveled their fields, to get them completely flat. An average rice field, says Isbell, will likely have a serpentine-style levee that holds water at different depths, which is needed for fields with slopes in different directions. With a flat field, “we more than have the amount of water that’s needed for [our rice] because you can so much more precisely flood the field without overusing water,” says Isbell. In that way, their rice may not be changing in the same way, but they are becoming more efficient, producing more bushels per acre on less water than 20 years ago. Isbell has, at one point, done the math down to the grain. “A high-water-use rice from another country is somewhere in the range of 14 cups of water to 400 grains of rice,”saysIsbell. “If you look at the mid-south, with average irrigation techniques, that’s maybe eight or nine [cups of water]. For the type of conservation practices we’ve implemented, we brought it down to about four or five cups of water [per 400 grains of rice].”

The view from a combine at Lundberg Family Farms. Photography by author.

The rice of the future

The benefits of healthy and efficient rice fields go beyond feeding the world. There are environmental benefits, with rice fields “acting as basically a sediment basin where the water is significantly clearer coming out of the fields than it was going in,” says Isbell. Producers will also often flood rice fields in the winter, which act as surrogate wetlands for migratory waterfowl. Lundberg farms estimates it has saved 30,000 ducklings in the last several decades of conservation efforts.

All of this work and effort is making a difference. Farms and varieties are getting more efficient, producing more rice with fewer inputs and less water. Breeders are finding combinations of rice that are more drought tolerant or capable of withstanding torrential downpours. And scientists are finding ways to strengthen all of this from within the DNA itself.

On the surface, all of this is good news for rice. But, there is a downside. Without a certain amount of variance within crops, they are more at risk of disease (take the Cavendish banana, for instance). Bergmann says it’s necessary to maintain a balance of crop diversity and predictive performance. “A farmer wants predictable performance; you want everything to mature at the same time. But from an ecosystem standpoint, variation is what gives a population strength,” he says. So, within their breeding schedule, they must account for time to let a variety “settle down,” taking years to go through successive generations of a bred variety to arrive at the right combination of variance and predictability.

Ultimately, though, no rice variety will stay exactly the same forever, no matter how many resources growers pour into it. “Rice will change,” says Jiang. “No variety will last for life.” That means those farmers, growers, breeders and researchers will have to keep innovating to stay one step ahead of future challenges.

Interesting article! I am glad to see much of the work being done by traditional breeding, not genetic modification; I find the potential danger of CRISPR and even earlier methods of genetic modification troublesome. I have been aware of the Lundberg brand for some time, and after this article, will be a more-regular purchaser; the research work they are doing is important. I don’t know the Isbell brand; will search that out as well.

Haven’t you all heard of dry land rice???

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-09-24/rice-grown-in-paddy-fields-climate-smart-crop/102861768

An interesting article. I am looking for a source for blue bonnet rice seed for sale for growing on my small farm. Is there anyone who can help me to source them?

Disappointed. I thought the article would be about all the new research into climate adapted rice. It is called *modern* farmer after all.