It’s been more than a decade since whole and 2 percent milk disappeared from US schools. A growing movement, spurred by dairy farmers, aims to reintroduce the beverage.

“Who likes chocolate milk?”

For the children in Greenville Central School District in upstate New York, the question is a no-brainer. Hands shoot up, and a chorus of eager voices cries: “Me!” “Me!”

Duane Spaulding reaches into a cooler on the back of his maroon pickup truck, grabs a handful of whole chocolate milks and hands them out to the gaggle of preschoolers. “It should taste like a melted milkshake,” he tells them with a smile.

It’s a rare treat for these youths.

America’s public schools last served whole milk in 2012, two years after Congress passed the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act. The law strengthened nutrition standards for meals provided through the National School Lunch and Breakfast programs, with the goal of increasing fruit and vegetable consumption and reducing childhood obesity and diabetes. Whole milk and 2 percent, with their higher fat contents, were casualties of the stricter guidelines.

But on this balmy day in late May, Spaulding, a former dairy farmer, and Ann Diefendorf, a sixth-generation dairy farmer from Seward, N.Y., are giving out whole milk on school grounds.

The two are distributing fliers touting whole milk’s nutritional properties at Ag Day, an annual event sponsored by the district’s Future Farmers of America chapter.

“We’d just like to get whole milk back in school as a choice,” Spaulding explains to the adults escorting children through Ag Day attractions. “So, if anyone can help, it’s a grassroots movement.”

One woman nods, scanning the fliers. “I completely agree with that,” she says.

This is the reaction Spaulding and Diefendorf want. The ban on whole milk in public schools is an ongoing source of discontent for dairy farmers and their allies in agriculture. They say whole milk is good for kids and that children will reject milk altogether and miss out on essential nutrients, such as calcium, potassium and vitamin D, if the only options are skim and low fat, which aren’t as tasty.

“I don’t want these kids in school thinking that’s the milk we produce,” says Diefendorf, who owns 45 dairy cows. “We produce whole milk. That’s what goes out in the milk truck every other day. And for those who are so far removed from the farm community, they don’t know.”

Spaulding, 64, and Diefendorf, 60, are involved with 97Milk, an all-volunteer organization seeking to reverse the ban on whole milk in public schools. Outreach and education are a core part of 97Milk’s mission, and the group’s name addresses one common misconception: the mistaken belief that whole milk is all or mostly fat. In reality, it’s only about 3.25 percent fat—“virtually 97 percent fat-free,” as the organization’s materials put it.

Duane Spaulding distributes chocolate milk to students from Greenville Central School District in upstate New York. (Photo: Sara Foss)

The intensifying activism around milk comes at a time of angst and anxiety for dairy farmers, who have struggled to break even for years as costs have risen and prices have slumped. Adding to the stress is that Americans are drinking a lot less milk.

While not a new trend—consumption has been dropping since the mid-1940s—the decline accelerated faster during the 2010s than in each of the previous six decades. Between 2003-2004 and 2017-2018, children’s consumption of milk and milk drinks fell 26 percent, from 1.07 cup-equivalents per person per day to 0.79, according to a 2021 USDA research report.

Data like this fuels concern that the dairy industry is losing ground with the youngest generation, the people who will become the customers of tomorrow. Also worrisome for farmers: The USDA is considering eliminating flavored milk in elementary and middle schools when it adopts new school nutrition guidelines for the 2024-2025 school year.

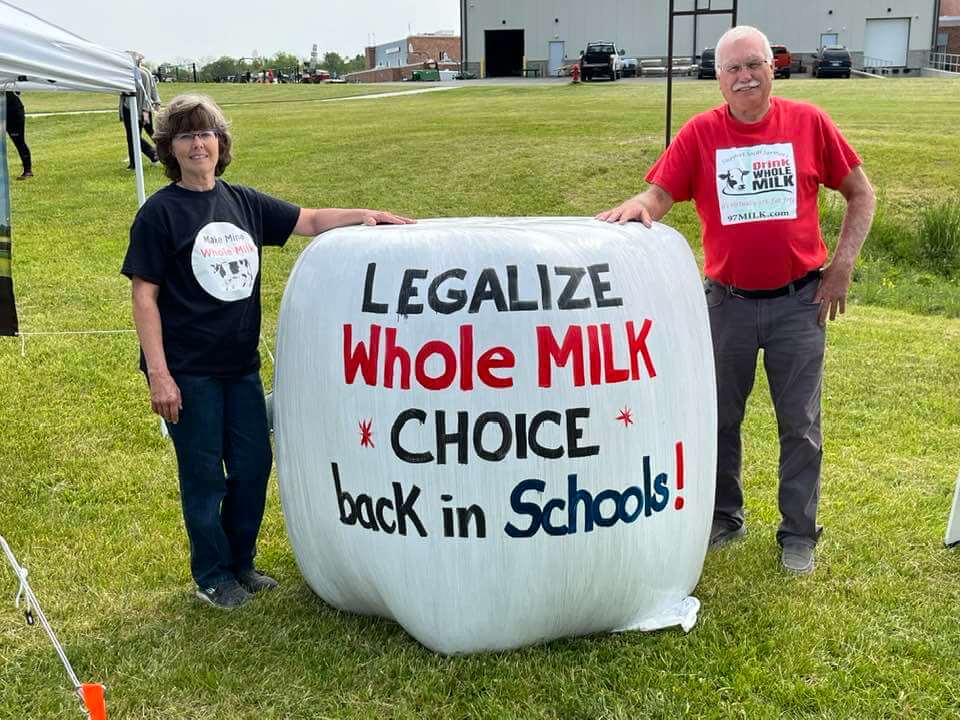

97Milk got its start in late 2018 when Nelson Troutman, a retired dairy farmer from Richland, Pa., placed a wrapped hay bale with a message urging people to drink local whole milk at an intersection near his farm.

Frustrated by a listening session with the Pennsylvania Milk Marketing Board—“they wine and dine the farmers, and then they go home and nothing happens”—Troutman decided to take matters into his own hands. “I said, ‘I’m going to start advertising that milk is 97 percent fat-free,’” he recalls. “I can paint that on a hay bale. It will look neat.’”

The bale did look neat. It went viral online and spurred media coverage. From there, organizing began, and hay bales began to proliferate. There are no formal records of how many bales have been painted or where they are, but Diefendorf estimates she has painted at least 50 in upstate New York. A 2022 article in Lancaster Farming reported that pro-whole signage had been spotted in at least seven other states, including Kansas and Ohio.

“The kids in school get skim, and they hate it, and they throw it away,” says Troutman said. “Our big thing is: Where is the nutrition? It’s in the garbage can.”

The resistance to reintroducing whole milk and 2 percent to public schools comes from health organizations that say skim and low-fat milk have the benefits of whole milk without the empty calories of the creamier beverage’s saturated fat.

Samuel Hahn, a policy co-ordinator on the school foods team at the Center for Science in the Public Interest in Washington, D.C., says school meals have become much healthier under the nutrition standards enacted in 2010. He says there’s little evidence that kids prefer whole milk to skim and low and that the research suggests what children really want is chocolate milk.

“What matters a lot more [to kids] is whether the milk is flavored as opposed to its fat content,” says Hahn. “As an organization, we’re not opposed to having flavored milk in school meals. We’re not opposed to milk at all. We just want to make sure it’s fat free or low fat, and if it is flavored, that it’s low in added sugars.”

“What matters a lot more [to kids] is whether the milk is flavored as opposed to its fat content,” says Samuel Hahn, a policy co-ordinator at the Center for Science in the Public Interest. (Photo: Shutterstock)

While leading health organizations, such as CSPI and the American Academy of Pediatrics, recommend children switch to low-fat and skim milk at the age of two, there’s disagreement within the broader health community on the merits of that advice.

“From a nutrition standpoint, whole milk is a great source of nutrients and really isn’t the problem with childhood obesity,” says Beth Chiodo, a registered dietitian who serves as public relations chair for the Pennsylvania Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

Some studies “have shown that kids who drank whole milk were at a reduced risk of being overweight and less likely to be obese,” Chiodo continues. “A bigger driver of childhood obesity is high-fructose corn syrup, snack foods, processed food and fast food. These foods are calorie dense and aren’t providing any of the necessary nutrients kids need.”

In its brief existence, 97Milk has gained some powerful political backers.

Earlier this year, U.S Rep. Glenn “GT” Thompson, a Republican from Pennsylvania, and Rep. Kim Schrier, a Democrat from Washington, introduced the Whole Milk for Healthy Kids Act, which would allow unflavored and flavored whole milk to be offered in school cafeterias. This is the third time Thompson has introduced the bill, which has 100 co-sponsors from 37 states. In June, the House Education and Workforce Committee approved the bill in a 26-13 vote. The next step is to schedule a vote by the full House of Representatives.

Similar bills have also been introduced in New York and Pennsylvania, where 97Milk is most active.

“Banning whole and 2 percent milk was an ill-advised policy change,” says Rep. Chris Tague, a New York state assemblyman whose district includes Schoharie County, where Spaulding and Diefendorf live. “It has not served our young folks well, and it’s also hurt our dairy farms.”

Tague, a former dairy farmer, is a co-sponsor of a bill that would put whole milk and 2 percent back in New York schools by allowing districts to serve milk produced by New York farms. Supporters contend that such milk has not entered interstate commerce and is outside federal jurisdiction. It’s unclear whether the bill, if passed, would survive a legal challenge.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, published every five years by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, recommends that those two years and older limit their intake of saturated fat to less than 10 percent of calories per day. If schools were permitted to serve whole or 2 percent milk, it would be difficult for them to menu these items regularly and still meet strict federal limits on calories and saturated fats. Thompson’s bill would increase the amount of saturated fat allowed in meals to account for the milk fat in whole milk.

During Diefendorf’s visit to Greenville, she painted an 800-pound bale to donate to the district during breaks from greeting children and handing out milk. The slogan: “Look Up 97Milk.com. Support Dairy Farmers.”

For Deifendorf and Spaulding, it will be a busy summer attending community events, fairs and other outdoor gatherings to share their message. The reception is overwhelmingly positive at Greenville Central School District, where many children come from farming families.

“That is really good!” one boy yells after sampling the chocolate milk.

“Of course,” says Spaulding. “We brought nothing but the best.”

We need whole milk back in the schools. We need chocolate milk back in the schools. These “guidelines” came during the Obama regime, at the behest of the President’s wife. Funny, their kids didn’t attend a public school. Many complaints about older students not getting enough for lunch, and many instances of students discarding foods they wouldn’t eat.

Chiodo is correct! Hahn and CSPI have an agenda.

I love milk and believe it is a good choice, not chocolate milk, disgusting chocolate milk or flavoured sugared milks. Why does it have to be chocolate milk. Why not full on healthy whole fat milk?

I agree whole milk and an hour of outside activity right before lunch.

Only raw whole milk is advisable to drink. The alternative; pasteurized/homogenized whole milk is dangerous and unhealthy and nothing more than processed junk.