In his new cookbook, Zacchary Bird offers a guide to transforming vegetables into flavorful meat-like meals.

As more people adopt a plant-based diet, the language we use to describe veganized meat dishes continues to evolve. We have vegan “cheese”, chick’n wings and jackfruit pulled pork BBQ—all made without animal products. Some hint at the modifier ingredient used, such as Tofurky, a plant-based turkey usually made from tofu. Others, such as cauliflower steak, use the language of meat to describe a vegetable dish.

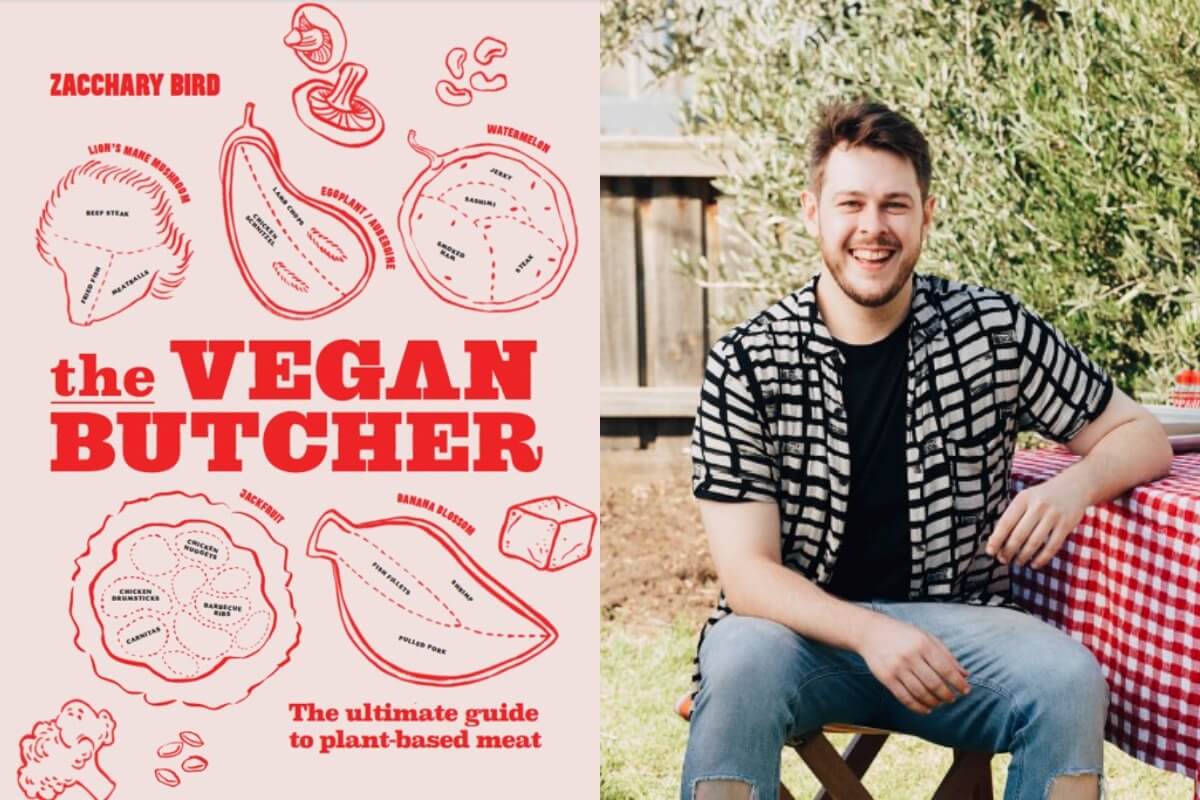

Cookbook author and longtime vegan Zacchary Bird embraces this sort of association. In his new cookbook, The Vegan Butcher: The Ultimate Guide to Plant-Based Meat, Bird provides vegans, as well as other eaters looking to consume less meat, with the techniques to make meatless cuisine taste like, well, meat. He includes plant-based versions of classic meat-centric dishes such as roasted turkey, pork belly, Nashville-fried chicken and Korean barbecue ribs, as well as vegan seafood, featuring oyster mushroom scallops, watermelon and eggplant sashimi and Baja fish tacos. The recipes graduate from basic to advanced recipes in each chapter, ranging from store-bought options to making everything from scratch. Bases include vegetables, proteins, legumes, seasonal fruits, mushrooms and more.

Don’t get too hung up on the meat-centric terms used in some of the recipe names—everything in the book is vegan. As food writer Alicia Kennedy pointed out in one of her recent newsletters, the words we use to describe vegan foods are bound to be tied to meat. “Our culinary language is based on meat; as more people move toward plant-based diets, there will be a period of overlap as we come to new or redefined terminology,” she writes. “Just as we’re adapting our diets because of changes in the weather, we can adapt meat-centric language to apply to vegetables where it makes sense without getting too tied up in what exactly the dictionary definitions are of things like ‘ribs’ or ‘butcher.’”

Before the release of The Vegan Butcher, we caught up with Bird to discuss vegetable butchering, meat substitutes and the future of plant-based eating. And as a treat, he shared a recipe for mushroom steak frites with us at the end.

The following interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Modern Farmer: People generally associate the word “butcher” with meat, not vegetables. Why did you choose the title Vegan Butcher for your cookbook?

Zacchary Bird: The name and cover design really captures the book’s mission: to showcase the versatility of what modern plant-based ingredients and techniques look like through familiar meals that look, chew and taste like you’d expect to be off the menu for vegans! The recipes range from simple and traditional—like homemade tofu or mock duck from bean curd skin—to an entire three-layer vegan and gluten-free turducken so that anyone looking to replace meat can find dishes in there that get them excited.

MF: Despite it being a vegan cookbook, a good number of the recipes have meat-centric names. What was the thinking behind naming them after their meat counterparts despite the proteins being substituted with other items?

ZB: Instead of telling people who are used to having fried chicken on a Friday night to have a bowl of lentils, the book is trying to offer a direct vegan substitute for familiar favorites. I wanted the recipe names to focus on explaining what we’re recreating. The book also offers a myriad of ways to replace each ingredient to really drive home the point that you can take flavors from non-vegan dishes and match them to similar textures for fantastically similar results. For example, the Nashville-fried Chicken can be made from seitan, washed seitan, tofu, okara, cauliflower or mushrooms.

MF: Will vegan food ever be able to step out from behind the meat-centric terms used to describe the way it tastes?

ZB: For sure, and it will! But we’re still in the stage where (at least according to my comments on social media) people don’t understand why a vegan would make food that tastes and looks like meat. Vegans haven’t given up meat because of its awful flavor or texture. It’s because they want to eat more ethically, environmentally friendly or (if you want to!) more healthily. It’s a simple fact that people have nostalgia for food they grew up eating, so I don’t think it’s shocking that we try to find better alternatives for them—and until we come together as a society and agree that one single ingredient is the best substitute, such as tofu for chicken—the easiest way to explain what we’re making is to compare it to what it’s trying to be an analogue of.

MF: What are some of your favorite techniques for transforming vegetables into a meat-like dish?

ZB: Smoking, charring and searing are all lovely ways to get a bit of burn in there. Vegan meals tend to be veggie-centric, which doesn’t hold up to long cooking times like meat does to get all that smoky flavor. So things like using a smoker box on your [grill] or introducing liquid smoke [to a dish] can be a great shortcut to that flavor with plant-based food. A good marinade loaded with umami (soy sauce, mushroom, sun-dried foods, fermented foods, miso, etc.) will help add in the rich savoriness often lacking in vegan alternatives.

MF: You include diagrams that show how eggplant can be cut and transformed into chicken schnitzel-like and lamb chops-like meals. Are there other fruits or vegetables that have those sorts of parallels?

ZB: They make such a great parallel to those classic cross-sections butchers have showing the different cuts of meat against the silhouette of a cow. I really wanted to invite the reader to think of plant-based ingredients in this same way as we explore which substitutions work for which animal product. The book has step-by-step images of the “butchering” process of ingredients being prepared as plant-based meat. For example, if you can get your hands on fresh banana blossom (as opposed to the canned stuff popular in vegan seafood recipes, which is also covered in the book!), I show you how to separate the leaves—which are inedible but great to serve things on—then separate the florets and remove their bitter components to be used as pulled pork. Then, we get to the heart of the blossom, which can be sliced up fresh in salads or, as I prefer, marinated, beer-battered, fried and then served as battered fish with hot chips and tartar sauce.

MF: If there were only one concept or idea to take away from your cookbook, what is it?

ZB: The versatility of plant-based options! I didn’t want to just tell readers to make a bolognese out of crumbled seitan, when I know lentils and walnuts, home-made or store-bought plant-based minced or even rehydrated textured vegetable protein (TVP) make a great meat substitute…so I put them all in! I hope that having multiple options to use as the base for each instills the idea that you can really explore and find your favorite alternative for a particular meat instead of trying the first one offered and deciding you don’t like it. There’s no one official way to do it and that’s wonderful news for a crafty home cook.

Photo courtesy of publisher.

Mushroom Steak Frites

Mushrooms and potatoes don’t need much more than technique to put on a rather convincing impression of steak frites.

Serves 4

Ingredients:

2 large lion’s mane mushrooms

Sea salt and black pepper, to season

1/4 cup red wine

1 tablespoon soy sauce

For the frites:

3 pounds, 5 ounces of large russet potatoes, unpeeled

Sea salt, to season

Canola oil, for deep frying

Instructions:

For the frites, fill a large saucepan with cold water. Slice the potatoes into your desired thickness. Add the fries to the water as you go, replacing with fresh cold water when done. Set aside to soak for at least 4 hours. Drain and place the fries back in the pan, cover with fresh water and season generously with salt. Bring to the boil over high heat and cook until the fries are just soft enough to pierce. Drain in a colander, then dry completely using a clean tea towel. Transfer to the freezer to fully cool and firm back up.

Heat the canola oil in a large heavy-based saucepan over medium–high heat to 300°F on a kitchen thermometer. Working in batches, add the fries to the hot oil, turning the heat to high just after they enter the pan. Loosen the fries with a slotted spoon, then fry for 8–10 minutes, until they form a light crust. Transfer the fries to a plate lined with paper towel. When dry, return the fries to the freezer to cool completely (reserve the oil).

Heat the oil in the pan to 375°F. Working in small batches again, cook the fries for 5 minutes until golden and crisp. Line a large bowl with paper towel and transfer the fries to the bowl. Toss lightly, then discard the paper towel. Immediately throw an obscene amount of salt over the fries and toss everything in the bowl.

Meanwhile, halve each mushroom horizontally through the middle to make thick steak-shaped slabs. Season with a good crack of salt and pepper.

Preheat a large frying pan over medium heat and add the mushroom. Sit a small heavy-based saucepan on the mushroom and press, allowing the mushroom to simmer in its own liquid for 5–8 minutes. Remove them from the pan, leaving any charred pieces behind.

Combine the red wine and soy sauce, then deglaze the pan with it. Allow to bubble for 2 minutes until thickened. Return the mushroom to the pan and coat in the wine glaze for a further 5 minutes. Serve immediately with the frites.