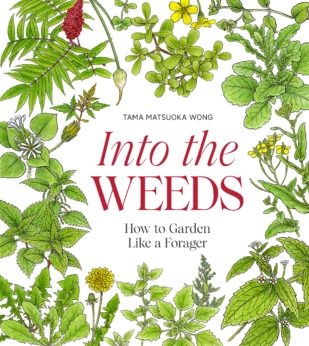

Tama Matsuoka Wong’s new book, Into the Weeds, is an invitation to change the way you look at what grows around you.

The summer I was 18, I worked a few hours a week on a small farm just outside of Portland, Oregon. It was a perfect gig for between school terms—I would help harvest things for the farmers market, pick weeds and occasionally round up a turkey that had escaped its enclosure.

Surrounding the immaculate rows of kale that sold well in downtown Portland, some “weeds” would pop up in bunches. My boss told me to pick these plants, called lambsquarters, to make way for the kale, but said that I should feel free to take them home and eat them, as they were actually delicious. I did—there were a lot of nights that summer that I had steamed lambsquarters on top of herby rice and lentils or in a stir fry.

Why couldn’t we bring these into town to sell at the farmers market? It had nothing to do with the taste or nutritional value—lambsquarters are on par with the best of greens. But, simply put, there was no market for these “weeds.” They weren’t trendy like kale, nor did they have an old standby reputation like spinach. And so, even though they grew abundantly without being planted, most of them just went to the compost pile.

Tama Matsuoka Wong’s new book, Into the Weeds, out March 12, resurfaced my memory of lambsquarters with a new curiosity. Not only does she mention them, she lists them as one of the top species to forage. Wong is a professional forager, finding, growing and collecting edible plants, many of which are considered weeds by the general population. She sources many of these plants from her own land—letting plants grow where they prefer instead of in orderly crop rows—and sells them to top restaurants in New York City, pulling them out of the “weed” category and onto dinner plates. After reading her book, which includes experiential knowledge, reflections, how-tos and a handful of recipes, I couldn’t wait to ask her more about her process.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Modern Farmer: There’s a term you use in your book that we should define. What is a “wild garden”?

Tama Matsuoka Wong: You might think that “wild” and “garden” are kind of contradictory to each other. But I mean, a garden in the larger sense of things is really anything that you can tend and enjoy—I think it’s something you relate to. So, a “wild garden” I view as something that is less created and controlled by you, and it has a lot more of its own initiative. I feel like it’s more dictated by the plants and their behavior. I’m not saying 100 percent, but it’s less of a cultivated garden, which is almost all created and planted by a person.

Brassica rapa, also known as Field Mustard. (Photography by Ngoc Minh Ngo)

MF: You forage foods such as lemon balm, chickweed and nettle, and your buyers include some very nice restaurants in New York City. What is the significance of creating a market for something that many people perceive as a weed?

TMW: I want [the work that I do] to become part of the food system. And so, in that sense, an easy way to start with that is to start with restaurants. It’s a very interesting creative [research and development] effort to kind of take something that some people might not be familiar with and make it taste delicious, right? Chefs just love that.

That being said, a lot of the plants that I am referring to are culturally significant. And in those countries, they are already culinary. And so, if I bring that to a chef who is from that place, they’re like, “oh my gosh.” To them, it’s just like home sweet home. That’s also what I think is great—people bring it as part of their culture. So, that’s what’s exciting about it.

The big difference is to try and really have these weeds or these plants make [their] way into the actual food system so people become more familiar with it. But it’s also something that eventually is pretty easy, and I think that’s happening. I see it at farmers markets, for sure.

MF: Is there anything that Modern Farmer readers can do to help some of these plants make their way into the food system more consistently?

TMW: If you go to a farmers market, ask the farmer for some. I’m sure they’ll recognize them and they’ll be happy to sell them to you.

Left: Ajuga. Right: Dried herbs for tea. (Photography by Ngoc Minh Ngo)

MF: Many people “weed” their gardens. You practice something you call “editing.” What’s the difference and how does it relate to stewardship of the land?

TMW: Weeding, usually, you just go and get rid of everything, because [you] think it competes with the crop. Which maybe some weeds do, but a number of weeds actually don’t and they actually help the soil. Like purslane and chickweed—they’re very shallow-rooted, so they actually help to prevent erosion and keep moisture in the soil. I’ve talked to soil scientists, and I actually know some organic farmers, family farmers, and they’ve used chickweed as their cover crop.

So, weeding, I think is [the] tearing, ripping out of anything that is not your crop. And editing is I’m making room for the weeds that I want. And I’m just editing out the ones that are less preferable. When I’ve talked to ethnobotanists, they said that that’s how peoples have worked with the land, is that they’ve edited out things for the preferred plants, always.

MF: In the book, you talk about your process, and instead of deciding ahead of time where to grow something, you often observe the natural habits of the plants in your space and take their lead. How do you balance that with the “business” of it all—needing to fill quotas for restaurants and the like?

TMW: I actually think it’s aligned. Because if a plant is growing where it wants to grow, it’s gonna thrive and multiply. If you’re trying to plant the plant where it doesn’t really want to grow—and believe me, you can try it over and over and over again—it’s just gonna sit there like a little sad, caged-up animal. And so, if you’re putting it in a place that breeds fecundity, as long as it’s not an invasive plant, then it’s going to thrive a lot of times. So, I think it’s aligned.

I do not plant invasive plants, because there’s so much of them that I don’t need to plant more. And actually, it would cause a lot of problems in my garden. But there are plenty of places that you can go and talk to conservation groups and others that will help you pick or let you pick invasive plants.

Left: Open-lashed edging. Right: Honeysuckle. (Photography by Ngoc Minh Ngo)

MF: For Modern Farmer readers who are intrigued by the idea of foraging, what’s a good first step or takeaway?

TMW: One of my tips for gardeners or farmers or people that look askance at whatever this wild patch that they may have is to make it look intentional. The second thing is that I don’t think I can underscore how important it is to realize that every little patch of earth is unique. The urge to just come and get rid of everything that’s there without looking at it, and then plant everything in—what you’re doing is you’re taking something that’s actually a cloned or propagated thing, and you’re getting rid of the things that are really unique and special about whatever that little patch of earth that you’re attending has.

If you don’t have access [to land], get to know your neighbors. If you know your neighbors, a lot of times, they’re not going to want the things that you’re going to want. The other thing is that there’s a lot of fallow land, and you need to make sure you’re working with the property manager, to make sure they haven’t sprayed or poisoned or there’s not a history of dumping or anything there. So, I’ve seen on the back of like church yards or temples or even areas of office space, there’s all this fallow, unused space. And you could go there and be like, can we have a garden, and then maybe have like a little bed, but then on the side, there’ll be weeds and you could forage those.

If you really can’t even do that, then just have some big containers in your window, and put dirt in it and see what comes up. Because people have sent me things from their balcony steps in Harlem, and they’re like, “We planted a tomato plant that didn’t come up, but what is this?” and it was upland cress! It was really good.

You don’t have to have all this time, you don’t have to go to a national park. In different levels, you could start in many ways.

Left: Phlox. Right: Seed collecting. (Photography by Ngoc Minh Ngo)

Into the Weeds comes out March 12. For interested foragers, this book provides some guidance on identifying and preparing wild foods such as lambsquarters, chickweed, sumac, purslane and juniper.

If you begin foraging, it’s important to do so safely, sustainably and ethically. Here is a checklist to help you begin.

As Wong says, you don’t have to go far. This interactive map can help you find forageable items near you.

Good sharing!